Throughout success and turmoil at Ibrox in recent seasons, the sight of James Tavernier running up and down the wing has been one constant.

Therefore, Tavernier’s positioning a couple of weekends ago in Rangers’ 2-0 Scottish Cup victory over Hibs stood out. Rarely, if ever, have we seen the full-back move infield as often as he did in Leith.

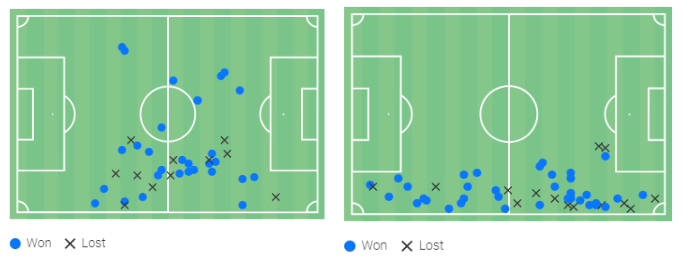

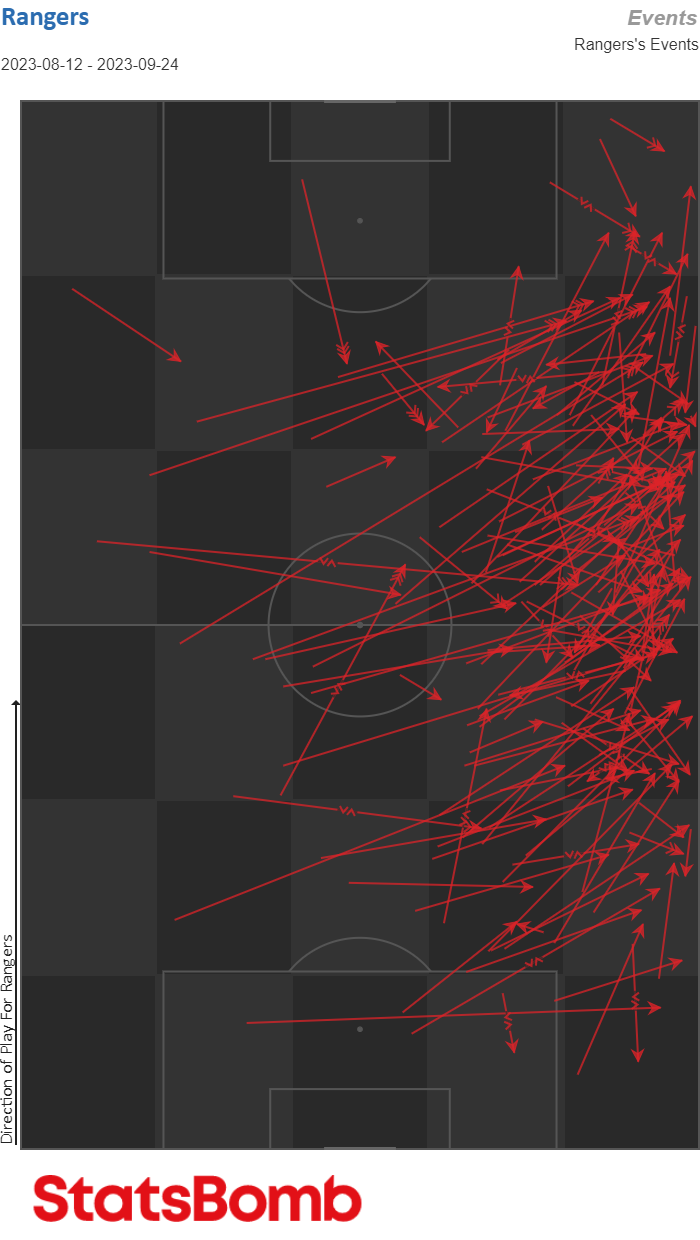

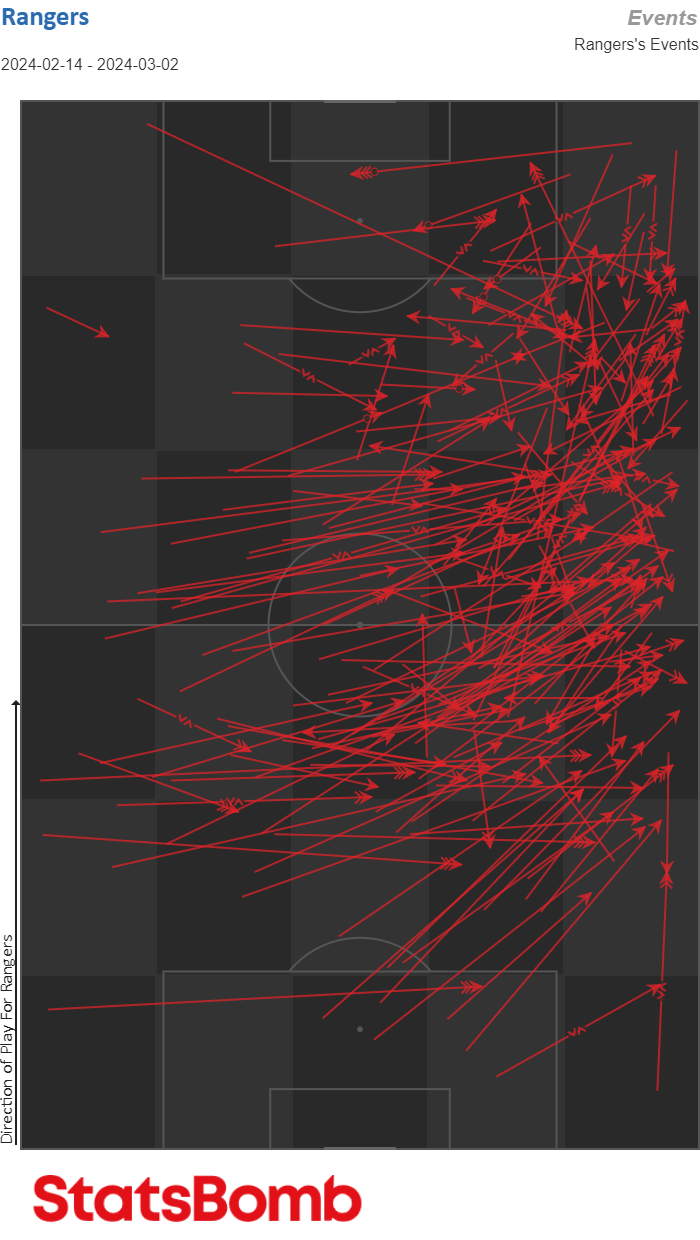

Comparing his touches from that trip to Easter Road in March 2024 (left) to Rangers' visit in May 2023 under Michael Beale (right), the contrast in clear.

The two games represent an overall shift in the role of the Rangers captain since Philippe Clement arrived. Away from the overlapping full-back function generally assumed in eight previous seasons at the club.

So, what is going on?

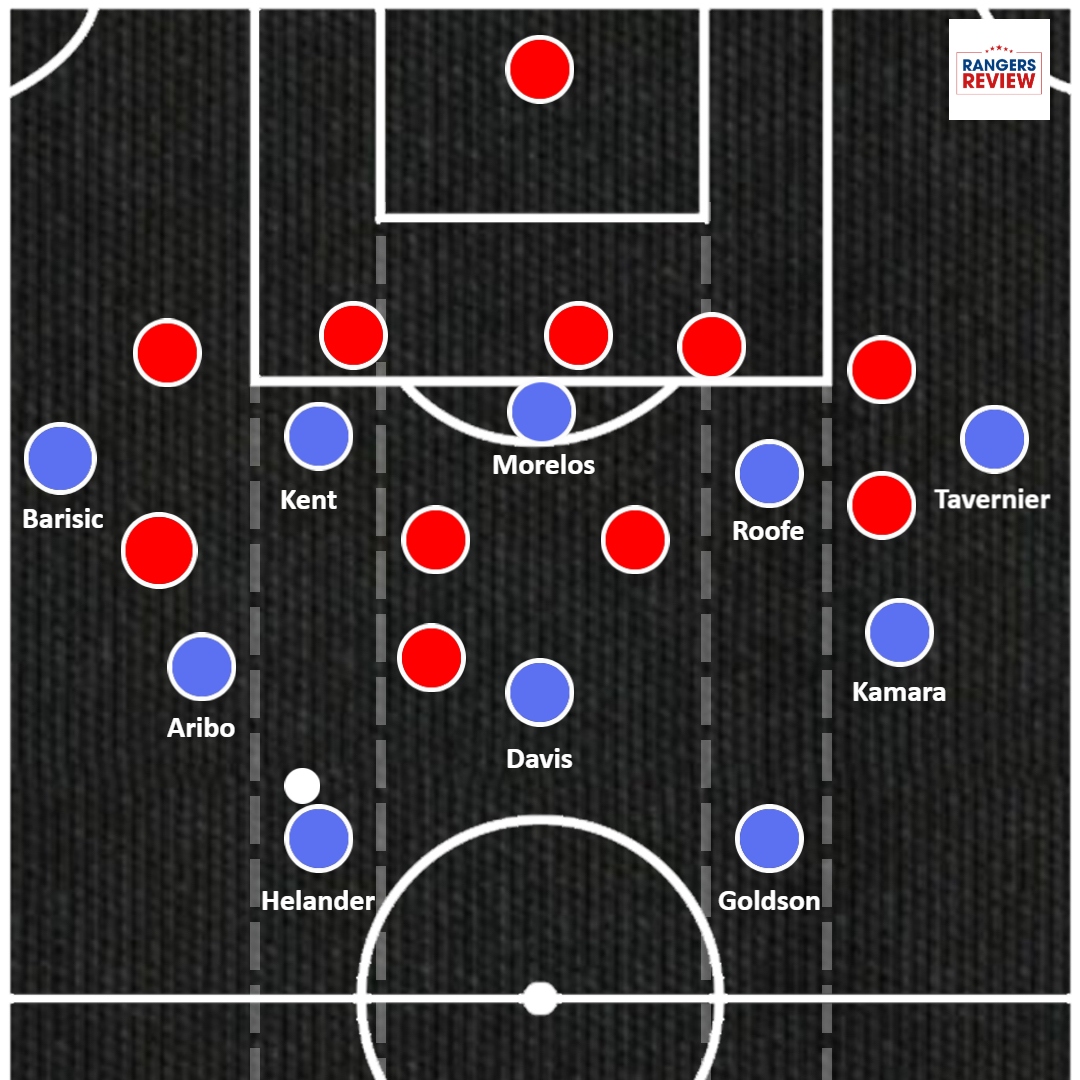

Spare a brief spell under Giovanni van Bronckhorst when operating behind a winger, the 32-year-old has played as a width-provider on the right flank. Since Steven Gerrard's arrival in 2018 Rangers have spent all but one summer recruiting for a tactical template that relied on full-back’s providing width, with wingers, especially on the right flank, few and far between.

It’s been the default across different managers and differing ideas for Tavernier to occupy the widest zone of the pitch and allow a gluttony of narrow, attacking midfielders to play in the inside channel, known as the half-space, instead.

That template has now flipped, with Tavernier inverting in the opposition’s half behind a winger.

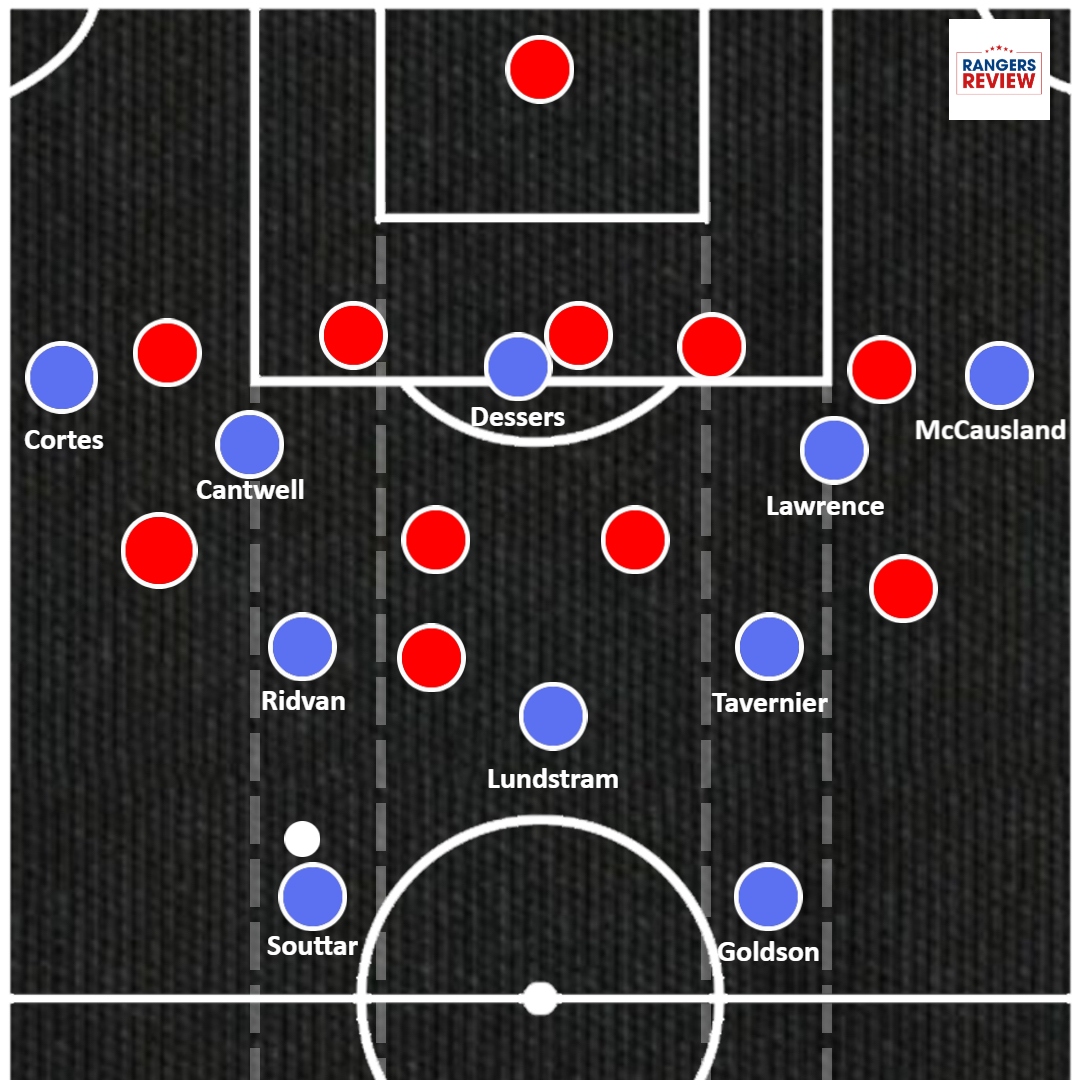

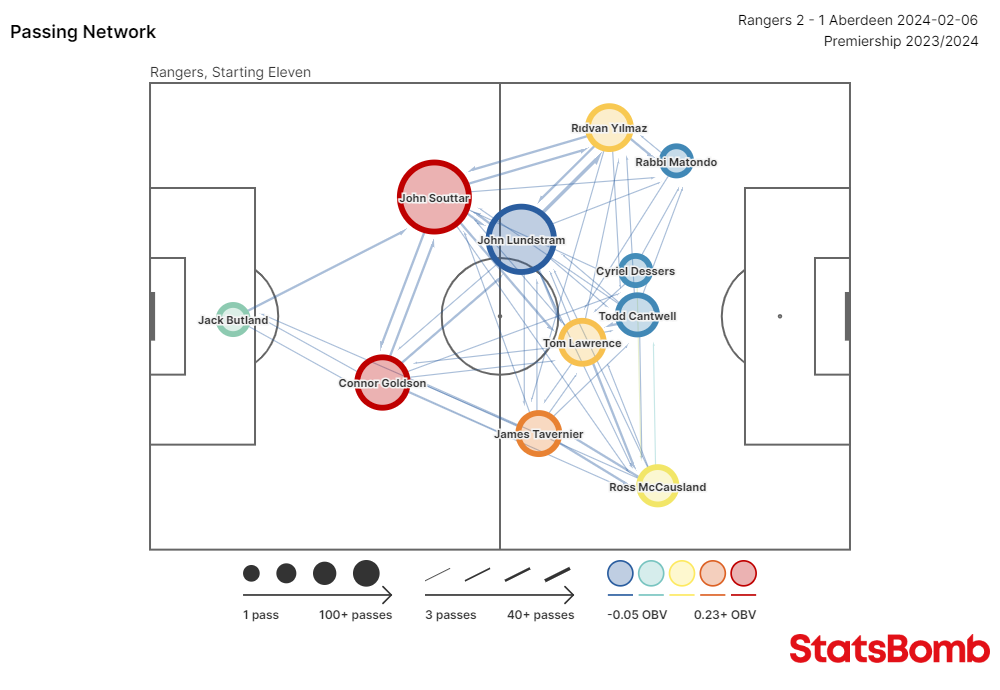

Clement’s football, when compared to predecessors, is faster, more focused on progression than possession and full of forward runners. The 4-2-3-1 base shape he favours is outlined in the below pass network, charting average passing positions from a recent 2-1 win over Aberdeen.

Notice a narrow Tavernier behind Ross McCausland, stationed wide on the touchline. An attacking midfield trio is enabled by the deeper starting positions of each full-back.

The full-back position has, arguably, undergone more tactical evolution than any other singular role in recent years. First they were overlapping pacey extra attackers, think Jordi Alba at Barcelona, to enable narrow wingers. Then, as football became increasingly transitional and defences more compact, managers started to push full-backs inside as extra midfielders, protect the centre against counterattacks and enable tricky wingers to stretch defences, think Philip Lahm at Bayern Munich or Joao Cancelo at Man City. More recently, again popularised by Pep Guardiola, we’ve seen top teams play nominal centre-backs at full-back as the boundary lines between zones and positions have continued to blur. Ben White at Arsenal and Nathan Ake at Man City are both good examples.

Trent Alexander-Arnold is another relevant case study. For years he was Jurgen Klopp’s wide outlet on the right but has, especially this season, played more centrally in the opposition's half while Mo Salah’s undergone a similar shift in the opposite direction. Rangers are no exception to the rule, as Tavernier explained during an exclusive sit-down with the Rangers Review in January.

“Right-back has evolved a lot,” he said. “Across football, you still see a lot of different playing styles. You've got aggressive inverted full-backs like Pep, who even has centre-backs moving into that position. Or Trent [Alexander-Arnold] who moves infield while the left-back at Liverpool, Robertson or Tsimikas, remains wide. It is constantly evolving.

“I know the current manager [Clement] doesn’t want to be too far open on when the ball is on the other side so that’s why you’ll see me tucked in. That also means I can get the ball inside the pitch, and protect against transition.

James Tavernier exclusive: 'Run through walls' for Clement, captaincy and adversity

“In the past, the manager wanted us high and wide no matter what side the ball was on which means centre-backs are prone to the counterattack and maybe have less cover. Now, the gaffer wants us to be a bit more secure and I am happy with that. Whatever the manager wants to do I will always adjust no matter what.

“Playing narrow gives security and the option of me finding passes from inside the pitch. I like overlapping and changing positions but you can do all that throughout the game when it’s the right moment.”

Here are the successful passes Tavernier received in the first three league home games of the season, under Michael Beale.

And here are the successful passes Tavernier received in his most recent three home league games, under Clement.

Notice the distinction between both pass maps. Tavernier is still wide when Rangers build play to stretch out the opposition and speed up that phase of the game before moving into narrower positions, to guard against counterattacks and open up passing lanes to the winger.

In the final third, Tavernier’s on the end of more backwards passes rather than through balls, passes at the edge of his box and is in general receiving closer to goal. This is, as he suggests, enabling him to find passes inside the pitch and operate closer to goal while still changing positions at the right time.

As Tavernier reasons, there are on and off-ball justifications for moving full-backs infield. Structurally, the move is motivated by Clement’s desire for wingers and runners on the last line and full-backs to protect against transitions. Decreasing the distances they must recover to form a defensive unit. The two phases in football are not separated - how a team attacks informs how they defend and vice versa.

Let’s take a closer look at the impact of this tactical shift.

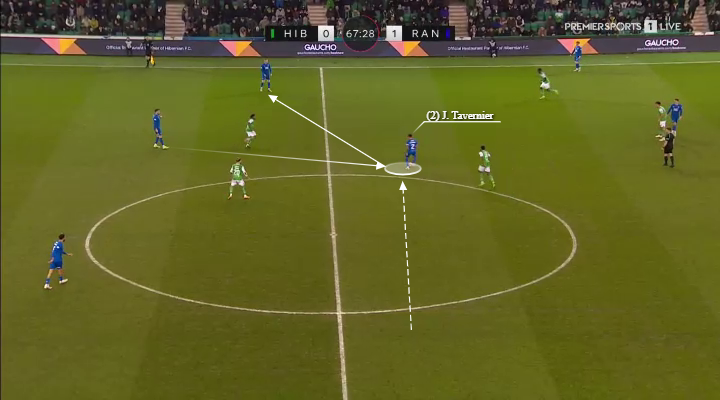

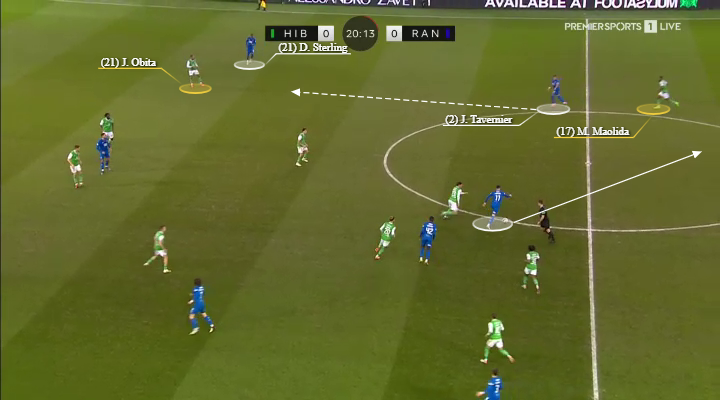

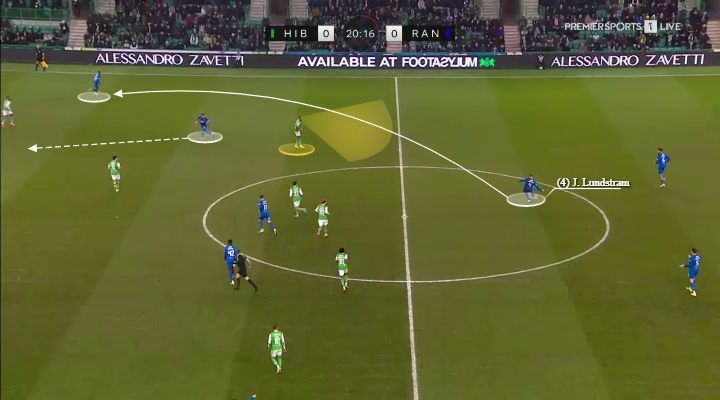

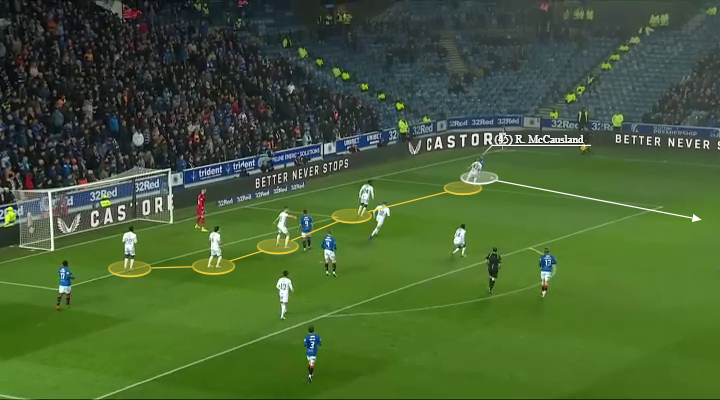

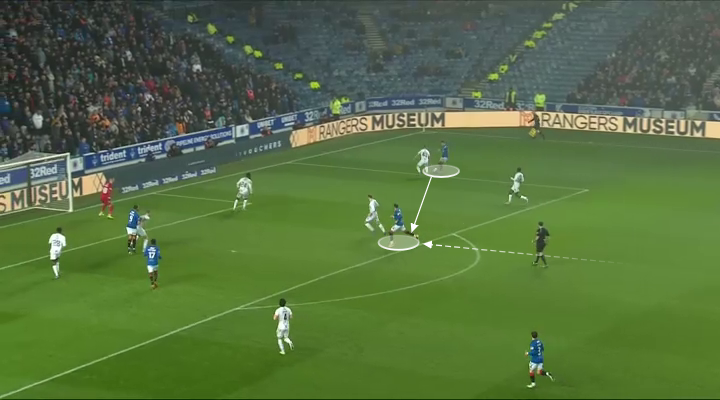

Revisiting the aforementioned meeting with Hibs, Rangers’ penalty won on the night shows some key principles at play.

As the visitors work from left to right, Tom Lawrence plays a backwards pass to John Lundstram. Tavernier gets a run on his marker Myziane to move inside the pitch while Dujon Sterling pulls wide from his right-wing berth.

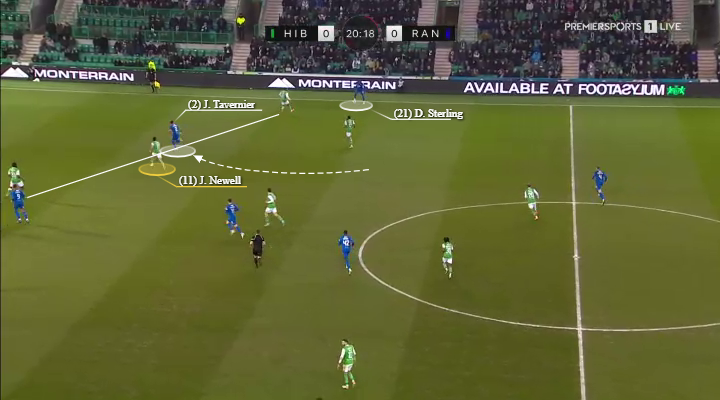

This allows Tavernier to make a seam run, targeting the space between full-back and centre-back. Jordan Obita, Hibs’ left-back, in theory can’t leave Sterling free, at risk of allowing the ball to be received by the winger in an advantageous area with momentum. If starting a left-footer on this side of the pitch, the pass into Tavernier could be played first time given Rangers’ rotation has been perfectly timed. It’s important to remember that Rangers# squad was constructed for a different style of play. Summer recruitment should allow Clement to play with round pegs in round holes, in this regard.

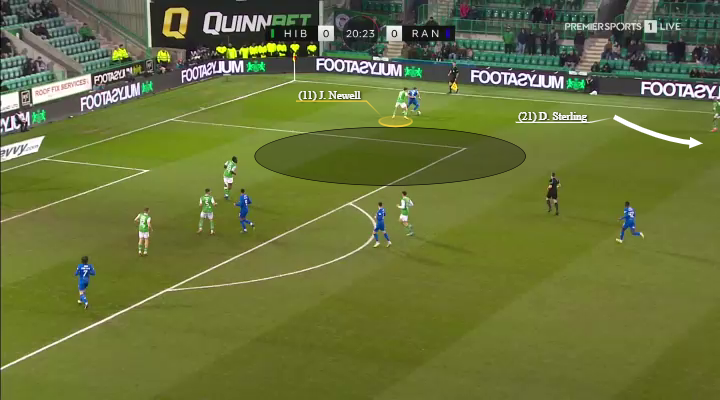

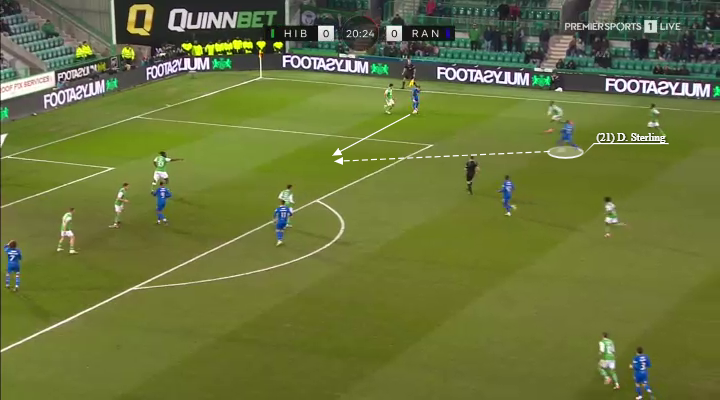

Sterling, unable to find a quick pass inside, plays in Tavernier down the line. Joe Newell, in dropping into the left-back zone, has left that seam position between Rocky Bushiri at left centre-back and the left-hand side vulnerable. That’s the area Sterling will arrive into ahead of Obita who makes a clear foul leading to a penalty.

In theory, during settled periods of possession against low blocks, wide wingers will provide a greater threat one-on-one to destabilise defences and create space elsewhere. Meanwhile, the infield runs from full-backs and midfielders in tandem should exploit these gaps quickly from the centre.

“If there are two players I have a look at, it’s Trent and Kevin de Bruyne. They get in those positions deep on the right and they’re whipping balls into the far post on the floor,” Tavernier added on the positions he assumes and players he models.

"Our games are different up here. We’re often playing against a block so you won’t get that opportunity to hit space. It’s about me perfecting the tools I have and continuing to grow.”

Watching football with James Tavernier: Striker's instinct, Beckham and back post

A recent 3-1 home win against Ross County probably offered the best example yet of the tactical benefits of playing Tavernier closer to goal.

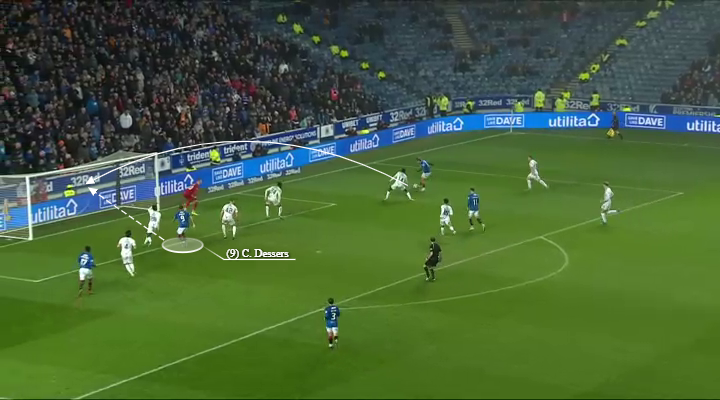

Operating behind a winger allows Tavernier to get on the end of ‘relay’ crosses from the half-spaces, very akin to the style De Bruyne has made famous at Man City. The reason these crosses are so dangerous is that defences are not set. As shown, they often squeeze up when a winger plays backwards, giving the crosser a corridor to target.

Look at the space opened up by the time the ball is played to Tavernier in this example, able to then hit a two-vs-two in the box as Rangers nearly score in the first minute.

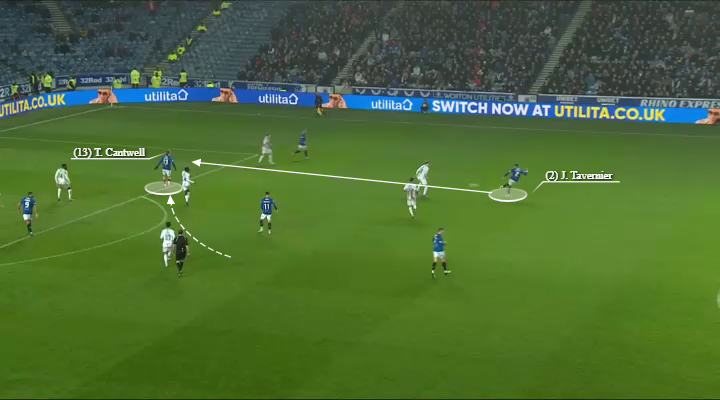

Tavernier was able to find passes inside the pitch like this ball for Todd Cantwell, which created an excellent back-post opportunity for Cyriel Dessers.

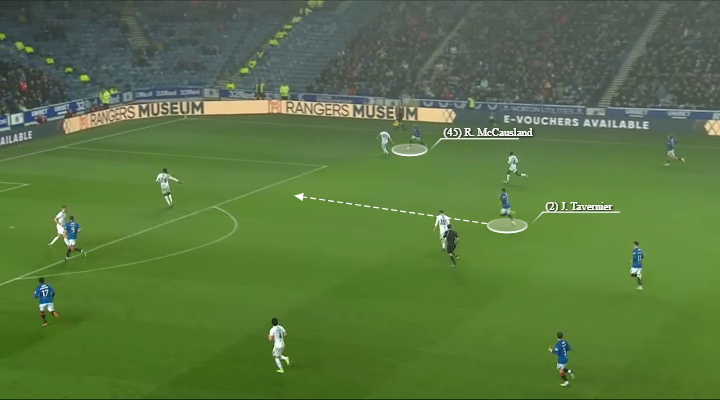

He could also attack the box and assume some threatening positions of his own, while McCausland stretched the backline and offered a wide threat.

While still alternating positions with McCausland in the right moments, this for one of his three assists in the game.

All while protecting against transition and assuming these narrow positions off the ball. As the home side created 4.88xG, Rangers relentlessly kept their opponents penned in with narrow full-backs and constantly stretched their defence with forward runners.

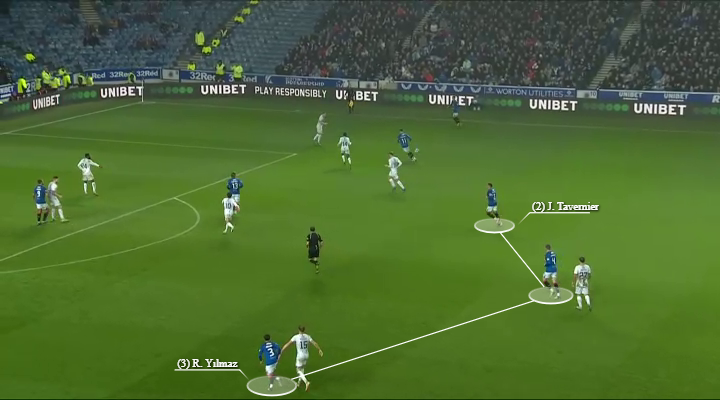

As the Rangers Review covered recently while the defence has been guilty of conceding a few cheap goal this calendar year the quality of chance conceded per game is up there with the best in recent years. A large reason for that fact is the positioning of each full-back to protect against transitions. Look at Tavernier and Ridvan Yilmaz stationed either side of John Lundstram in this example.

“The gaffer bangs on about when we are attacking our organisation behind the ball. I think we are so much less prone to counterattacks, we manage to play in waves and keep the ball in the opposition half. Being able to strangle teams when they come here,” Connor Goldson recently said on this topic.

“That's the way he wants to play, every time a ball is cleared it has to be us first and counterpress as quickly as we can. Then at home, he wants us to strangle teams and get them as far back as we can. Making sure we get wave after wave, we're limiting counterattacks and I think that was our problem before, we were conceding too many chances on the break."

As Clement’s Rangers evolve and improve, while full-backs inverting in their own half may not be all that common, Tavernier and Ridvan's occupation of central areas in the opposition half will. To open up wide passing lanes, protect the centre and create closer to goal.

In many ways Steven Gerrard got it right and wrong when discussing how to fit Tavernier and Nathan Patterson in the same team.

“It’s not a big strength for James [receiving with his back to goal]. If we use this system James will be more out wide where he is used a being, Where he is when he plays right-back. I certainly won’t play him as a 10 with his back to goal.”

Tavernier isn’t playing infield all that much in the build-up. Nor is he operating frequently with his back to goal. It’s unlikely the future sees him move infield to receive in a pivot position. The full-back is still wide in the build-up and under Beale, when the team was functioning as planned, Tavernier had the ability to move infield in the right moments.

Inverted full-back is not a one-size-fits-all phrase and there’s too much variation to Tavernier’s game to say he’s made a complete rebrand.

It is safe to say, however, that Tavernier's role has evolved more than ever under Clement. And the new role seems to suit him.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here